Will a gender critical barrister feel free to express her views in the workplace? Those of her client in court?

This post is written by one of our members who wishes to remain anonymous. She is a non-practicing solicitor.

The last few years have seen a profusion of legal cases brought in the UK courts and employment tribunals to protect the rights of women and children. In particular, Maya Forstater successfully brought a discrimination case against her employer to defend her gender-critical (GC) beliefs, which resulted in them being protected as beliefs under the Equality Act 2010.

This legal victory, and others ranging from protecting rape victims, to free speech in universities, has been pivotal in protecting gender critical beliefs under English law and affirming that biological sex matters in policy and public life. Many cases relate to potential ambiguity in the Equality Act 2010, and the recent trend reflects how courts and tribunals in the UK have to grapple with balancing the rights of individuals to express sex realist beliefs and the possible impact on others.

However, our ability to use the courts and employment tribunals to shape the British landscape further may be under threat.

Recently, the Bar Standards Board (“BSB”) opened a consultation aimed at changing Core Duty 8 of its handbook, which states that barristers must not discriminate. The proposed change would wholly replace this entirely sensible duty and, instead, require barristers to actively “advance equality, diversity, and inclusion” (EDI) in their professional conduct.

The BSB’s proposal has been framed as an essential step to further promoting fairness and inclusion within the law. However, the proposed new Duty is concerning for many reasons; the ones set out below are merely a few.

Firstly, there is a distinct lack of clarity as to what the proposed Duty amounts to as the draft Code does not clearly define what EDI means nor how a barrister is to demonstrate their compliance. The new Duty certainly appears to extend well beyond the scope of recruitment and purports to attempt to apply to barristers in their legal practice.

Let’s turn to a client wishing to instruct a barrister and a barrister wishing to accept a brief. Arguably, a lawyer could have reservations that a gender critical client’s views might conflict with EDI; therefore, receiving a brief from such a client could pose a risk for a barrister in striving to adhere to the new Duty. GC clients could face a scarcity of barristers willing to act for them. This is of grave concern.

Currently, it is fundamentally accepted that barristers, under what is informally known as the “Cab Rank Rule”, are always obliged to take a case in a field of law in which they have the requisite level of legal competence, provided the client can pay their fees and that the barrister has time in their schedule to do the work. Embedded in this rule is a clear principle of non-discrimination; whether by reference to a client’s identity, cause, or merits of the case.

The Cab Rank Rule applies where a client holds views with which a barrister may well disagree. This ensures access to justice even when the case is controversial or unpopular so that clients can find legal representation. The new Duty attempts to shift the goalposts and arguably empowers a barrister to decline to accept a brief that doesn’t meet ambiguous EDI criteria. This entirely conflicts with the Cab Rank rule so that specific clients could be discriminated against.

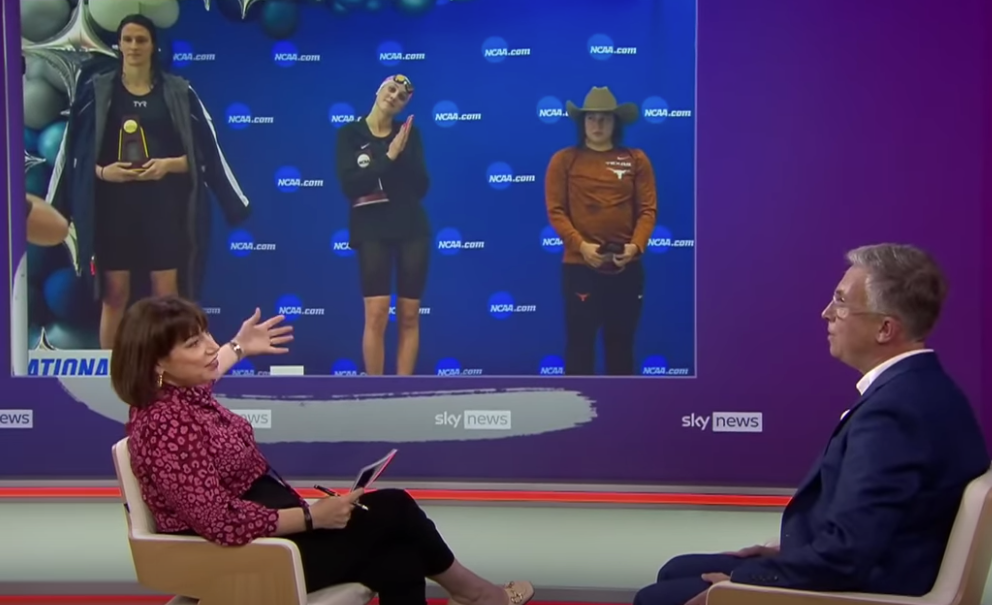

One could easily imagine a scenario where a barrister subject to the new Duty could feel uncomfortable about taking on a brief relating to gender identity ideology, fearful of even running legal arguments in favour of sex realism in court. The legal debates crucial to protecting women’s spaces, safety, and fairness may be perceived as conflicting with EDI's “prevailing” views.

A barrister may be concerned about potentially breaching the new duty when arguing that, for example, one group with a protected characteristic (women) takes priority over another under the Equality Act, in particular circumstances. We all know that conflicts between groups with competing protected characteristics are inevitable, and courts are often where these conflicts are resolved.

The courts and the legal teams representing all sides must remain independent and impartial so that there is a forum for resolving these disputes fairly. Barristers should not be constrained or concerned when deciding whether to take on a brief, and they should certainly not be obliged to consider whether a brief meets EDI targets.

Even if a GC client manages to find a barrister prepared to act for them under the proposed Duty, the chance of a successful court outcome could be reduced. It is unclear how, for example, a barrister would be able to freely advocate on a GC client's behalf or cross-examine a witness openly without fear of breaching the EDI parameters.

The costs involved in bringing any legal action are already significant; GC clients may be even more reluctant to opt for the judicial route or to appeal a court decision if an environment of fettered advocacy further diminishes their choice of counsel and their prospects of success.

Newly qualified barristers and those in the early stages of their careers seeking to establish themselves and build their practice could be particularly susceptible to forced compliance with the new Duty to retain a blemish-free record and avoid disciplinary actions. As to more established barristers, what would become of those who may well feel that they do not subscribe to the highly contested values of EDI? It is unclear how barristers holding GC beliefs will act under the proposed Duty.

By encouraging a barrister’s devotion to EDI, the BSB seems to be pushing legal professionals towards adhering to a prescribed set of political beliefs rather than championing the diversity of public debate. As Conservatives, we value freedom, fairness, meritocracy, and individual responsibility, all of which are inconsistent with EDI principles and accepted social justice narratives. Let’s leave barristers free to provide robust legal representation to all clients, regardless of a client’s beliefs, a barrister’s personal views, or external pressures.

In a few weeks, the Supreme Court will decide on the appeal of the Judicial Review of For Women Scotland Limited to clarify what the Equality Act means at law for women. Future GC clients must have a fair chance of finding a legal team to represent them and a realistic prospect of a successful outcome, especially when this new Labour Government appears reluctant to clarify and protect women’s rights to single sex spaces and free association by bringing in legislation to rectify ambiguity in the current Equality Act 2010.

***

Please read and respond to the Bar Standards Consultation

here.